In my last post I wrote about how students react to being graded. Initially, that was supposed to be the opening paragraph to this post, but I got carried away. What I’d like to talk about today is how grades are presented.

For now, I don’t want to focus on how grades are assembled. Some educators may rely strictly on rubrics or use ungrading or just go off vibes. All of that refers to the process of quantifying assessment. I am interested in the way that process is presented to students once a class is over.

Traditional hierarchical letters

The first approach is the one you’re already thinking of: A, B, C, D, F.

Different places may add some spice to this. Failing may be at 50% or 60%. They might get rid of +/-. There might be a few fewer or few extra letters.

But ultimately you have an ordinal ranking of letters where everyone knows who did better and who did worse. You may disagree with the process by which the grade was determined, but the result presents a hierarchy of student achievement, at least from an institutional perspective.

One thing that often goes unstated is that this remains imprecise. Letter grades are not strict rankings of student performances, they are buckets of student performances.

The buckets, however, can be weirdly inconsistent.

As a society, we like to divide things into groups of 10. With the +/- grading system, this necessitates dividing 10 by 3 in order to have the grade of “A” be 90-100. In order to keep our grades in tens, schools often let the middle term (A, B, etc) cover a 4 point spread, while the +/- (A+, B-) covers a 3 point spread.

That may read like minutiae, but the bigger point is that this approach to grading simultaneously communicates precision and approximation. It typically is based on points collected over an extended period, a collection of assessments, and a measurement of performance against established standards. At the same time, student performances are lumped together into bands of letter grades, which are themselves distinguished based more on how the letter “feels” (imagine an A- being an 88%… inconceivable!) than on communicating consistent information about those performances relative to other students.

Newer hierarchical options

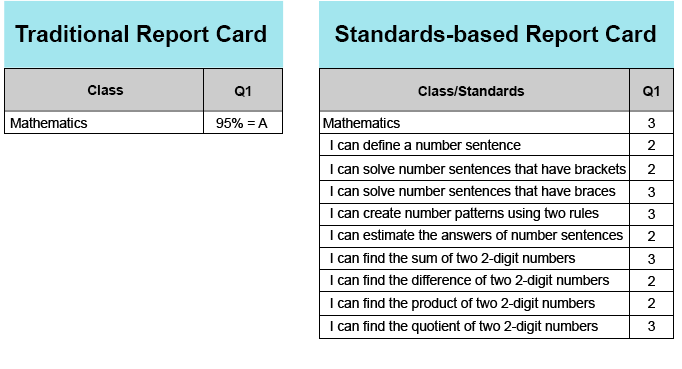

Another approach is one variously called “standards-based” or “mastery” or “performance” grading.

The idea is that instead of students earning (or losing) points throughout a term to arrive at a grade, they will demonstrate their ability to do different things. That ability will be assessed into buckets (but these are different buckets), sometimes numbered 1-4, sometimes explicitly labeled with words like “beginning,” “proficient,” or “excelling.”

One thing I like about this approach is that it does not set “exceeding” as a standard. In traditional grades, every student starts the class with 100% and slowly loses points to drift down from an A+. In standards-based grading, you work “up” to mastering a subject, but it’s not expect for students to exceed. In fact, it’s supposed to be rare. This can also do something for grade inflation, where students come to see anything lower than an “A” as a failure.

But in spirit, how different is this? While the institution may state that a “3” is proficient and normal and a “4” is rare, that doesn’t mean they stop issuing 4s. Students will realize that a 4 is higher than a 3 and they will be led to ask delightful questions like “Why did she get a 4 and I didn’t??” They may come to think of themselves as the kind of student who “can never get a 4 in math.”

And at that point we’re not so far from where we started. They may be calculated differently, but any ordinal ranking of performance like this is going to have similar effects on students.

Keep grades secret, keep grades safe

Another approach would be to simply not tell students their grades at all.

Noting the tendency of students to fixate on grades, to the exclusion of all other feedback, some colleges stopped telling students what their grades were. Reed College is typical of this approach, as is my alma mater, St. John's College. At these institutions, students are assessed on a traditional grading scale, but they do not get to see that hierarchical assessment. Instead, their faculty write detailed narrative assessments on student performances or meet with them individually to discuss their work.

This more complex form of feedback ostensibly serves to individualize the process and spur students toward growth no matter their grade. After all, many students who receive an “A” will tell themselves they have nothing more to learn from a class if feedback that points them toward areas of further development is not foregrounded. When they don’t know whether or not they got an “A,” that feedback is all they will have to latch on to.

Of course, the students do still get grades.

One of the ways these uncommon colleges justify their pedagogical innovations is by pointing to improved student outcomes. Take another look at that link from Reed. Alongside their descriptions of why they don’t tell students their grades, they point out how many students earn competitive scholarships and how many of them go to graduate school.

Those kinds of outcomes require grade reporting. So, the grades are stored on their transcripts and passed along when the time comes. Students will still see their grades eventually, but it may not be until after they graduate.

Binary grading

The last approach I want to mention here is one I witnessed in my doctoral program this year.

One of my professors was very clear about how he graded students. There were only three possible course grades: A, I, and F.

An “A” meant that you’d completed all your work.

An “I” meant that you had not yet completed all your work, but that you’d made a plan with the professor on how you would complete it.

An “F” meant that you had not completed all your work, and you were not going to.

If you got an “I,” the idea was that it would become an “A” once you completed your work or an “F” if you chose not to. So, really, there were only two possible grades: A or F.

If work you submitted during the course was not deemed sufficiently “complete,” you’d need to redo it and resubmit it, lest you risk the “I.”

One benefit I saw was this encouraged creativity. I knew that I had to complete each assignment, but instead of trying to cater my work toward my professor’s preferences to game my grade, I felt the freedom to try things my own way. With completion as the goal, I could treat the whole class as a totally personal learning experience, one in which I managed my own development. I knew that I would get an A anyway if I did the work, so the pressure was off and it was up to me to take advantage of the course.

This may rely on something unique about graduate education: self-direction. Unlike K-12 students, no one is forcing a student to get a doctoral degree. Binary grading can tap into intrinsic motivation because it asks students to take responsibility for their own development. But many K-12 students feel as if they’re being educated against their will, so I would be curious to see how this would play out in that setting.

Scale and specificity

One thing I want to continue to think about with all of this is the effect of scale on an institution’s pedagogical options.

For example, narrative assessment is possible at a place like St. John’s because there are 20 students in a class, and they all get lots of direct interaction with faculty. Would it be possible in a chemistry lecture with 200 students?

This may point to the fact that lectures in the triple digits are inherently poor ways of educating. I don’t really know. But what it certainly points to is the fact that small institutions and small classes have options for assessing students that get more difficult the larger they become.

Additionally, smaller institutions can more easily create buy-in around non-traditional practices like narrative or binary grading. The larger an institution becomes, the less experimental it must be in order to satisfy a wider swath of staff and students who will support assessment policy.

So, we could say that some grading systems, in a vacuum, are better than others. And they may be! But we should also ask which grading systems are pragmatic, intelligible, and politically acceptable across a wide population. If you believe that mass education is a public good, then that question is important too.

-Matt