In 2018, I read the Tao Te Ching. This is the foundational text of Taoism, one that has influenced people for thousands of years.

I thought it was pretty good.

I wanted to read more about what people did with that text, as I knew Taoism became institutionalized in ways that were not apparent in that founding text. So, I picked up a book from the Drake University library about two of the earliest extant commentaries on the Tao Te Ching.

I read every page of this book. I don’t remember anything beyond what I managed to write in my Goodreads review.

The book was very particular. It almost certainly wasn’t the second book I should have read about Taoism; much of it went well over my head.

That’s okay in itself. I don’t expect to recall every detail of every book I read. But in this case, I could feel myself forgetting what I was reading as I was reading it.

I think that’s because the subject did not have connective tissue with almost anything else I knew. It was basically a standalone title, and I did not reinforce it by reading anything else about the subject afterward. At this point, I remember having read the book, but that’s it.

I want to think about general education. When we require students to take a variety of courses across a variety of subjects, how similar is it to requiring them to read one book about ancient Taoist commentaries? And what’s the point of distributional course requirements anyway?

Individualism in the academy

Distributional requirements are best conceived as a curricular compromise between students, faculty, and university administrations.

For the first 200 years of American higher education or so, the curriculum was mostly set in place. College students would pursue a Bachelor of Arts degree by completing a set collection of recitations and tutorials. The subjects were determined by what would be most useful for a gentleman. Greek language was in, English literature was out.

While there might be differences between institutions, the broad brush strokes of the degree was very similar across the landscape. Students within a given college would all have very similar academic expectations.

This shifted in the 19th century (as so many things did), principally due to the increase in the college-going population which accompanied growing industrial wealth. But these children of industry (and their tuition-paying parents) wanted both the social credential of the college degree and for that academic experience to be more rooted in the “useful and practical.”

This resulted in the institution of the “Bachelor of Science” degree. This was a separate path from the BA which would allow students to pursue subjects (like chemistry or engineering or astronomy) which had not previously been central to the college experience. The greater flexibility of this degree drew increasing numbers of students.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the tide started to turn definitively. Charles William Eliot, president of Harvard (at the time, the largest college in America), eliminated almost all course requirements for graduation. While students still needed to complete a set number of courses, the construction of a graduation plan was entirely up to students themselves.

The thinking was that students would have a better sense of what they wanted to get out of college and would tailor their time toward the outcomes most important to them. Additionally, Eliot wanted faculty to be able to specialize their research and teaching toward the subjects they were best suited to. This meant individualized specialization for both sides of the classroom.

Compromises and consequences

Various stakeholders found this arrangement unsustainable. While some students used the opportunity to build a personally enriching academic experience, many did not. For students whose goal was primarily “being in college,” the elective system gave them permission to only take the easiest and most introductory courses available to them.

Even if this didn’t represent every student, the potential for taking this “master of none” approach to college did not reflect well on what the growing universities were trying to accomplish. Additionally, it was unlikely to gain favor with the families paying for their children to get a practical education. Faculty, too, wanted to train the next specialists in their discipline, as well as get enough students enrolled in upper-level courses to offer them.

But you couldn’t put the genie back in the bottle, so there had to be some balance between the absolute institutional control of the original curriculum and the absolute liberty of the new one.

The compromise is the “major” and “general education” models.

One way to think of this is as supplementary structures built on top of the free elective system.

A truly free elective system would say that you must take 40 courses to graduate (for example), and they may be in anything you like. The compromise adds a “but” to that sentence. It says that students can take any course they want but ten of them need to be in one subject in a sequence determined by a single department… but also ten more of them need to be in a range of subjects determined by the university.

When you consider that major courses may have additional pre-requisites, this makes over half the curriculum specialized (i.e. not free) by design. And once disciplinary credentialing is set as the outcome which validates a degree, taking courses for fun which count for nothing becomes less appealing. You might take a one-credit bowling course for fun, but it becomes harder to justify taking full courses with their lectures and tests and papers if they don’t count toward something “real.”

The mentality I describe here is exactly what the curricular compromise hoped to control. Students will almost never choose to take hard courses as an end in themselves. Therefore, the institution needs to direct student attention toward specialized credentials (like majors, minors, and certificates).

If these components of the degree are deemed to have more value than simply getting a degree, students are motivated to stack them. Why graduate with one major when you can get two? We quickly see our space for free electives dwindling due to the overlaying of specialization structures.

So, if free electives have a diminished role and specialized tracks are the dominant feature in undergraduate education, what’s that other thing taking up space over there in the corner?

Oh right, this post is about general education

According to the description I laid out already, general education is the set of requirements which don’t lead to a credential beyond the degree. These are requirements which apply to every student equally, and acquiring a degree implies having completed these requirements.

They are called “general” because they include requirements across a breadth of disciplines. There are many ways to design general education. Some institutions will have a “common core” with a set sequence of courses required of all students complemented by electives across other disciplines. But centralization becomes more difficult as the scale of an institution increases. It may be feasible for every student to take a three-course sequence at a college with 500 students, but it becomes increasingly difficult to get consistency and faculty unity when that same sequence must be taught to 5,000 or 50,000 students.

As such, the dominant model is “distributional.” What this means is that students are required to complete courses across a range of themes, but each theme’s requirements can be met by a range of courses.

Let’s look at an example.

General Education at IU

These are the general education (or “common ground”) requirements for all undergraduates at Indiana University. Each area requires one or two courses (except the two “world” courses, which can be substituted for one another).

The university justifies these requirements as necessary for producing well-rounded graduates:

“Regardless of major, career plans, or personal goals, all IU graduates should excel in the essential skills of oral and written communication, critical thinking, and quantitative analysis. Every student should leave IU with a broad knowledge of the social and natural world, a keen sense of self, an awareness of our membership in a global society, and understanding of what it means to be thoughtful and responsible citizens of the community, state, and nation in which they live.”

In two sentences, they’ve explained the rationale for the whole set of themes. You may rightly quibble with the idea that students will “excel in oral communication” after taking one hybrid-format public speaking course, but this is their intention.

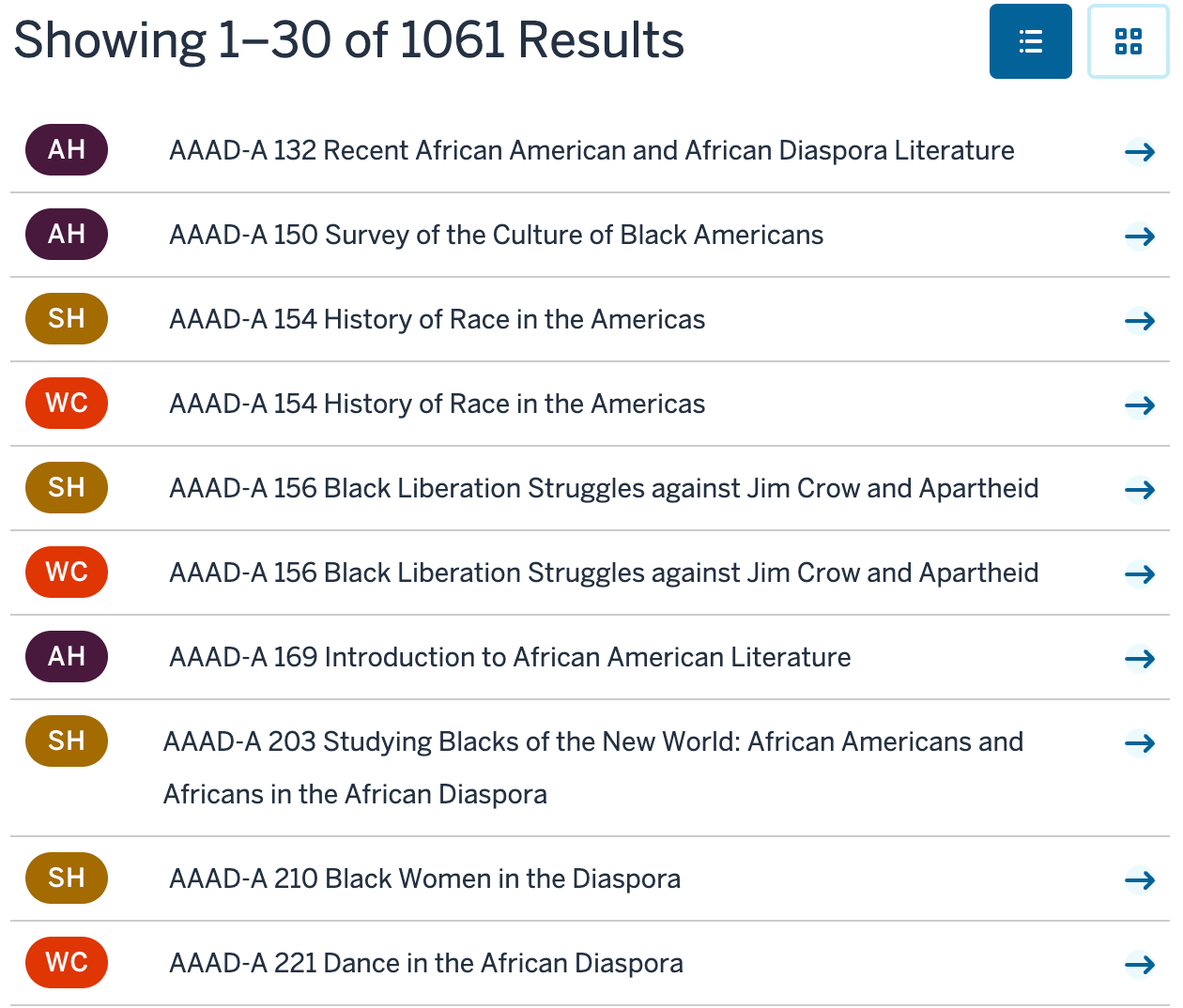

So if we have established that it’s difficult to have a single sequence for general education at an institution of IU’s size, how many options are we talking about here?

1061 options. A little overwhelming?

Some requirements are more restricted than others. There are only four options for “English composition” and 14 for “mathematical modeling.” Perhaps this indicates that the university actually has expectations for these subjects?

But the other themes are wide open. There are 232 “Arts & Humanities” courses, 132 “Natural Science and Mathematics” courses, 257 “Social and Historical” courses, and 422 “World Culture/Language” courses. Of course, these are just a sub-set of the total number of courses offered at IU, many of which are in the same subjects but are not deemed sufficiently broad or accessible to count for general education credit.

How can a student possibly navigate this web of possibilities? They have to use some personal shorthand: what class did someone I know take? What class do people say is easiest? What class is already in my major that I can get gen ed credit for? If I scroll long enough, what title will my eyes magically land on?

The question is whether “The Art and Culture of Modern Italy” and “The Black Death” and “Foundations of Journalism” and “Personal Health” are all giving students a “broad knowledge of the social world.” I would contend that taking these distributional courses are, instead, giving students a narrow knowledge of a social world.

So, why do it?

I mean, there are worse things than learning something random. My concern is that the experience is, in effect, like reading one book about Taoism. You may remember that you did it, but it was so specific and narrow that it won’t do much for you if it’s treated as a standalone subject in your degree.

I do think these general education courses can have some function. They help subsidize departments around campus by drawing in students from other departments who would, otherwise, never take a course in a given subject. They help the university maintain some claim to taking part in the “liberal arts tradition,” even if only by the most generous of definitions. It may even help students realize that it’s worth learning some things that aren’t part of a major. Occasionally, it will transform a student’s whole college experience.

But more often, I think distributional requirements like these function as student taxes. They are a tax on student time, energy, and money to support other university stakeholders. Students tolerate them because, in the scheme of things, they are not particularly onerous. But any increase in those general requirements would be fiercely resisted as taking the place of major (“useful and practical”) coursework.

Students also tolerate general education because it mirrors their experience in high school where taking courses in a range of subjects is mandatory. In fact, many of them will “test out” of general education requirements in college via AP tests or dual enrollment courses they did before arriving. This reduces general education requirements to expectations that you have, at some point, in some manner, done some kind of college-coded course about something related to a variety of subjects.

Is that enough to help students “meet the challenges and embrace the opportunities of life in the 21st century”?

Maybe it is! Or maybe it’s just a minor, forgettable speed bump.

-Matt

![Two Visions of the Way: A Study of the Wang Pi and the Ho-shang Kung Commentaries on the Lao-Tzu [Book] Two Visions of the Way: A Study of the Wang Pi and the Ho-shang Kung Commentaries on the Lao-Tzu [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4007da33-ab6f-486b-8178-f0a6b5b61d7d_880x1360.jpeg)

An essential discussion here. My take is that education should be as much about inspiration as information. Professors in all courses, but maybe particularly of the general ed courses, have a high calling to inspire their students to life-long curiousity. How this was able to happen I am not sure, but in 8th grade my social studies teacher spent the entire first month on the JFK assassination. Inspired me to drill through information and forever be curious about politics and American history.

Well written, Matt. The concept of this as a "tax" is new to me and a useful metaphor.

I also thought of another metaphor for general studies which involves throwing particular material onto a wall, just to see what sticks.

So much to talk about from this. Thanks