If you want to go to college in the United States, you have to pay for it. Or, at least, someone does.

At the moment, the FAFSA delay has demonstrated just how central federal student aid is to making the higher education landscape function.

Students are reliant on tuition aid largely because tuition levels have risen much faster than inflation. While some might blame financially reckless institutions for building lazy rivers and rock climbing walls, I think that’s too easy an excuse. The issue is that those institutions are charging what someone will pay.

It’s shocking to see a college say up front that it will cost $90,000 to attend. After they say that, they’ll often say something like “But don’t worry! Over 90% of students qualify for aid and pay less than full price.”

So then why set the price so high?

Give me the space to do my thing

If you set the price high enough that only a few people will pay it, the school has found their upper limit for tuition. I don’t want to be simplistic and say that universities only care about tuition as revenue because I don’t think that’s fair. It is one of many factors they care about, along with many facets of demographic compositional diversity and academic preparedness/likelihood of success in their program.

But if tuition is not the only consideration in building a class, it might be the biggest one. Budgeting depends on consistency in revenue streams, and particularly for the majority of colleges who have small endowments and depend on tuition as their primary revenue source, they cannot help but plan for student payments strategically.

What high tuition accomplishes is breathing space. A prospective student’s family might not be willing to pay full price, but what if the school offers you $10,000 off. Let’s call it a scholarship to stoke your ego a little bit.

In fact, if you offer families admission to two different institutions for the same net price, one where they are paying full price and one where the full price is higher but they have a “scholarship” to lower it, families are much more likely to choose the scholarship option.

It doesn’t matter if the price is the same; our brains process cost savings as an opportunity. So if you turn down that institution, you’ve “sacrificed” that scholarship. It doesn’t matter how you got it or why the institution gave it to you; it’s yours. And we hate giving away money, even if it was fake money that the school created on your behalf.

This is the same logic of baseball tickets or ride sharing services or rare book dealers. The thing they’re selling has no set, inherent value. It only has the value that the buyer is willing to ascribe. So the seller will adjust the price to maximize the number of buyers and total return.

It doesn’t matter if you have to take loans. Or if you get a scholarship. Or if you get a job. It only matters if you’re willing to enroll and find a way to pay what you’re asked to. At that point, it’s your problem.

Brand awareness

Federal funding, external grants, and loan forgiveness don’t actually address this issue. If tuition has become decoupled from reality, expanding and contracting only insofar as the public will balk, then finding different ways to pay the tuition that institutions demand will simply validate institutional practices of charging as much as they can and letting other people figure out what to do about it.

I am not sure that this is a crisis, per se. But it is certainly bad for the brand of higher education. Seeing prices for education as something totally variable, unpredictable, and seemingly random will not inspire confidence in it as a pathway to plan on pursuing. It encourages a shotgun approach from applicants where they apply to dozens of schools, treating it less like finding an academic home and more like a lottery.

Institutional alternatives

If we don’t want it to be about the money, maybe the only way is to take out the money?

There are seven four-year colleges in the United States that don’t charge tuition for any student. All academic costs are covered by other sources.

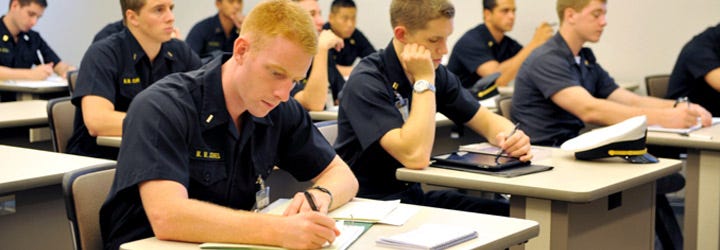

Five of the seven are federal military academies. There is no tuition because every student carries an obligation to complete federal military service following their graduation. The students don’t pay money, but they pay time instead.

The other two are Berea College and Webb Institute. Berea focuses on serving low-income students, primarily from Appalachia. Webb Institute serves… students who want to become ship builders. The thing they have in common is that both institutions are reliant on alumni donations to sustain their expenses. Both institutions have clear missions, missions that the alumni believe in and are willing to support for the next generation of students after them. Students may work for the campus while they’re there, but they will not and cannot graduate with a debt burden.

Expansions and contractions

My sense is that all seven of these institutions have something in common: mission.

Each of them orients their whole curriculum around an idea, what they’re there for and what kind of people they support. The specific circumstances of each of these schools is less interesting than the fact that they all know what they stand for. How many other universities can say the same?

Most colleges and universities don’t just expand their tuition because they can; they expand their mission because they can. Although most schools were founded with a specific charter of what they represented and who they existed to serve, that mission has grown to be inclusive of everyone who might possibly want to attend (and pay to do so).

Universities try to have as many academic programs as people will pay for, as many sports as students will attend for, as many ancillary services as the community demands. They will do as much as they possibly can, stand for as little as they can get away with, and look to the margins of each activity.

Perhaps we don’t have a tuition expansion problem. Perhaps we have a mission expansion problem. In an era when colleges are fretting over demographic cliffs and the potential for market contraction, maybe they will start to ask whether the meaning of the services they provide continues to have a self-evident interpretation. If these institutions cannot be convinced to contract their tuition independently, maybe they need to start by contracting their mission.

-Matt