I want to reflect briefly on the concept of the “paradigm.”

In social science research, this is a key term. Scholars tend to claim paradigms as the starting point for their inquiry. These are philosophies which, ostensibly, describe the author’s view of reality and how knowledge is constructed.

A scholar will often openly align themselves with a paradigm at the beginning of a paper as a sort of shorthand, letting their readers know some things about the kind of work they intend to do without needing to spell it out in detail.

Since I’m still working through this myself, this post will contain some more directionless musing than usual. I don’t want to pretend like I fully understand this topic. But I also don’t want to pretend like not fully understanding everything means I have nothing to say.

So now I’ll say some things.

What’s in a name?

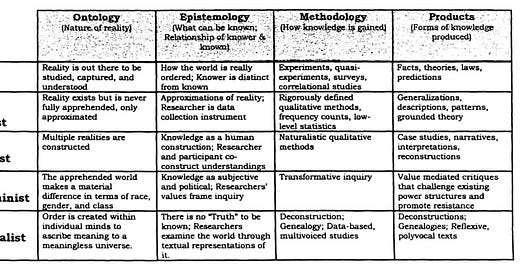

You can see one example in the picture above of how paradigms are distinguished. Of course, different texts will define them differently and include different categories.

In social science, one big reason for identifying with a paradigm is, in my opinion, to pass the vibe check.

Some paradigms are cool. Being a critical scholar is cool because you are interested in changing the world and liberating humanity. That’s good. We like that. Keep it up.

But positivism? Not cool. No one claims this paradigm. It’s so petty and workmanlike. Plenty of people use methods associated with positivism, sure. In fact, the majority of scholars are positivist in effect, but they would not be likely to claim it. Why would you? Do you not want to change the world and liberate humanity?

A paradigm is only stated when it makes the author appear more acceptable to their readers, often their disciplinary peers. Otherwise, paradigms are either left unstated or are purposefully misstated. I mean, we all want to change the world for the better, right? Maybe we can just call ourselves critical scholars for fun. Who cares?

Paradigms want to be exclusive

There are a few additional issues I have with “choosing” a paradigm.

The word, as it’s used, is derived from the work of Thomas Kuhn. He described the evolution of philosophies of science, focusing on moments of “paradigm shift,” where scholars went from understanding the world in one way to understanding it in another.

Think of the shift from a geocentric to heliocentric view of the solar system as an example.

This shift in paradigm would impact everything for an astronomer. It would affect every theory that drove their research and change how they understood their work. Most importantly, it would be impossible for them to be both geocentric and heliocentric. You could not believe the Earth orbited the Sun and believe the Sun orbited the Earth.

That seems obvious, but scholars will often talk about matching your paradigm to your work. So, depending on what you’re writing about, you may present yourself as interpretivist or post-structuralist or critical.

The issue is that if it’s possible to hold all of those paradigms and to shift between them at will, then they are not paradigms. Paradigms are mutually exclusive, and you can’t carry more than one in your heart.

Consequences determining their causes

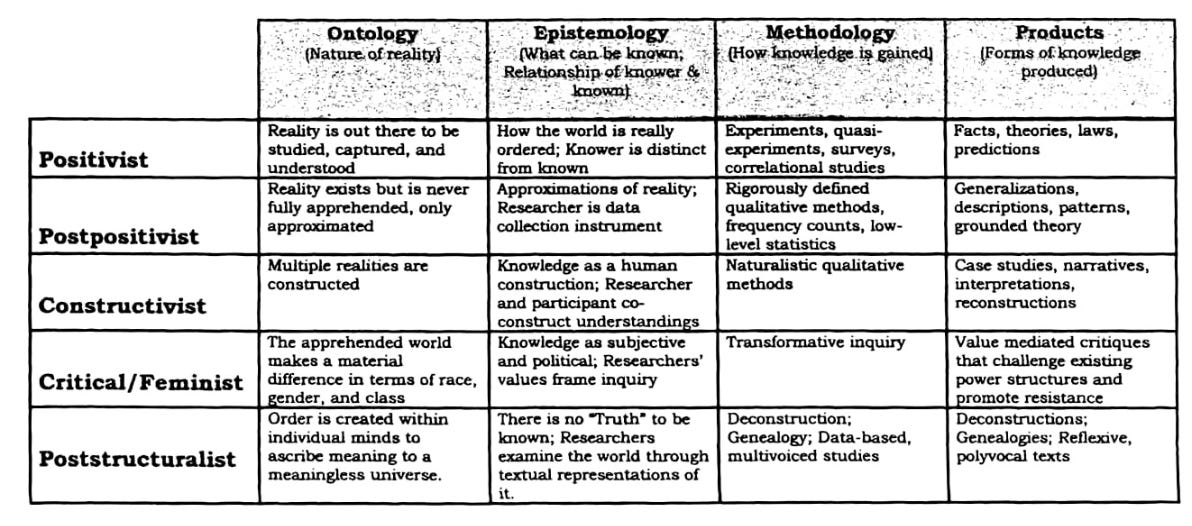

I want to show you another “paradigm breakdown” image:

You’ll see that each paradigm carries a set of methods under its umbrella. Most scholars will do work with more than one method at some point. So, if you want to do a survey, do you need to be a positivist? Can you do a case study without being a constructivist?

If you engage with a certain research question, some methods will be more useful for that task than others. The method you decide to use, then, carries a paradigm with it. This is another way in which scholars are expected to be multi-paradigmatic.

I have no opposition whatsoever to scholars conducting different kinds of research. It would be really boring if we were forced to only do the same kind of work in order to maintain paradigmatic purity. I want to use as many methods as I can.

But if paradigms really constitute your view of reality and the nature of knowing, can they shift with your methods?

After all, I can manage to hold the disparate purposes and assumptions of “interviews” and “linear regression” in my mind at the same time. I can understand how they answer different kinds of questions without seeing a contradiction in the nature of reality. No heavenly bodies are in overlapping orbits in my mind’s eye here.

So what are paradigms doing if they are not providing exclusive and absolute frameworks of reality for social scientists?

Paradigm as rigor

Earlier I said that adopting paradigms was a selective form of “cool coding,” where the scholar presents themselves as being right-minded to their disciplinary peers. I do think that’s a factor, but it’s also about “legitimacy coding.”

Think of how powerful the word paradigm seems. So weighty! This isn’t just an idea. Not a mere theory. No. It’s an all-encompassing, ontological, epistemological conceptual smorgasbord. It contains multitudes! And it’s very important.

Social sciences tend to face a threat of being perceived as soft, insubstantial, or trivial when compared to the sciences. Chemistry and physics don’t usually need to justify their value because they are studying “real stuff.” The kind of knowledge they produce looks and feels valid because it studies “the world,” the world of material.

Social science studies “our world,” the world of experience. This is a world of feeling, impression, and emotion. Because forces like gravity are observable by multiple persons, they are easier to validate than internal forces like feeling.

In an effort to legitimize social science, the study of feeling, to their peers in other disciplines, social scientists present paradigms as a way of signaling rigor. By aligning with a complex philosophical system, social scientists appear engaged in systematic inquiry. Even if social science will never quite look like hydrogeology, paradigmatic language makes it appear robust. It makes you appear scientific.

The paradigms’ paradigm

Okay, here’s the part where I make a contention of my own. The things we call “paradigms” are just big theories. Hierarchically, theories are situated within paradigms as ideas for engaging with specific concepts. Those theories then connect to methods for implementing research on specific kinds of questions.

You can hold a single paradigm and access many theories within that paradigm because each theory is just an idea that helps you give language to a certain problem.

Social science paradigms do that too. All of them probably carry elements of truth and help you engage with social questions in different ways. Each carries different norms and assumptions and traditions. Each gives you language for addressing different problems. Some theories may be broader than others, but every “paradigm” I’ve talked about functions like big theory because they are not mutually exclusive. Each “paradigm” can address different slices of the social experience in ways that are comprehensible to a single, undivided mind.

This doesn’t mean that social science lacks actual paradigms though. I think we have at least one of them. The issue is that no one knows what it’s called.

Because each so-called “paradigm” is mutually intelligible, they are contained within a larger “true” paradigm which enables their mutual intelligibility.

I contend that we cannot access the nature of this all-encompassing paradigm because we cannot see outside it. In the same way that we can’t see beyond the edge of the universe, we are contained within the social universe of a single paradigm. If we were to try to name it, we would fail because it is so foundational that it would transcend any effort to be simplified into nameability.

Something at the root of our “socialness,” our “communicativeness,” our “humanness” is a paradigm which underlies our ability to conceive and know a social world. But our capacity to be social is an internal phenomenon which predates naming and cannot be observed in itself. As long as we’ve been human, we’ve been bound within the paradigm of social life. It’s the only way we know how to be. It’s what binds every theory of human connection, and we can’t give it a name because we can’t “shift” away from this paradigm to anything else.

Social scientists, then, assign themselves paradigms because they want to be able to label a world view and show that their social science is science. The issue is that we have to substitute “big theories” for paradigms because our shared paradigm is too basic to be expressed. And if all we had were “ideas,” while scientists got “paradigms,” that would be a huge bummer.

So I’d guess paradigms aren’t going anywhere, even if they don’t deserve the name.

-Matt

I appreciated your discussion of paradigms as a heuristic for signaling legitimacy and rigor. However, I think that even the heuristic game is starting to run into friction in STEM - particularly physics. I came across an interesting youtube video about a paper recently published in Nature. It involves a science influencer, so caveat emptor, but I found the idea of a “bubble" in particle physics research to be an interesting concept, and gave me a bit of smug satisfaction as a social science research that always feels a bit of the “are you a real scientist” pressure in the back of my head. https://youtu.be/shFUDPqVmTg

I think you are on to something with the "paradigm" vs "big theory" discussion. If there is a paradigm behind the paradigm, is it really a paradigm? FWIW, this is also a major issue in management in the private sector. Lots of fuzziness (and lazy thinking, IMHO) on the topic which leads to uncertainty in leadership and communication. Thanks for sharing your thinking!