Standardized testing and the theater of merit

It doesn't have to be fair; it just has to make you feel like a loser if you fail.

In a similar vein to what I wrote about last week, I spent a part of my summer reading about standardized testing. Specifically, I read about Chinese testing in two books. The first, China's Examination Hell by Ichisada Miyazaki, focuses on the Civil Service Exam, particularly in its final form during the Qing Dynasty. The second, Meritocracy and Its Discontents by Zachary Howlett, is about modern China’s college examination system, the Gaokao.

The two books pair well together and paint a picture of a testing culture that feels very foreign at first blush. I think that, perhaps, those differences might be less substantive than they appear. What the Chinese tests attempt to do is part of an enterprise of social cohesion that appears much more familiar than I expected.

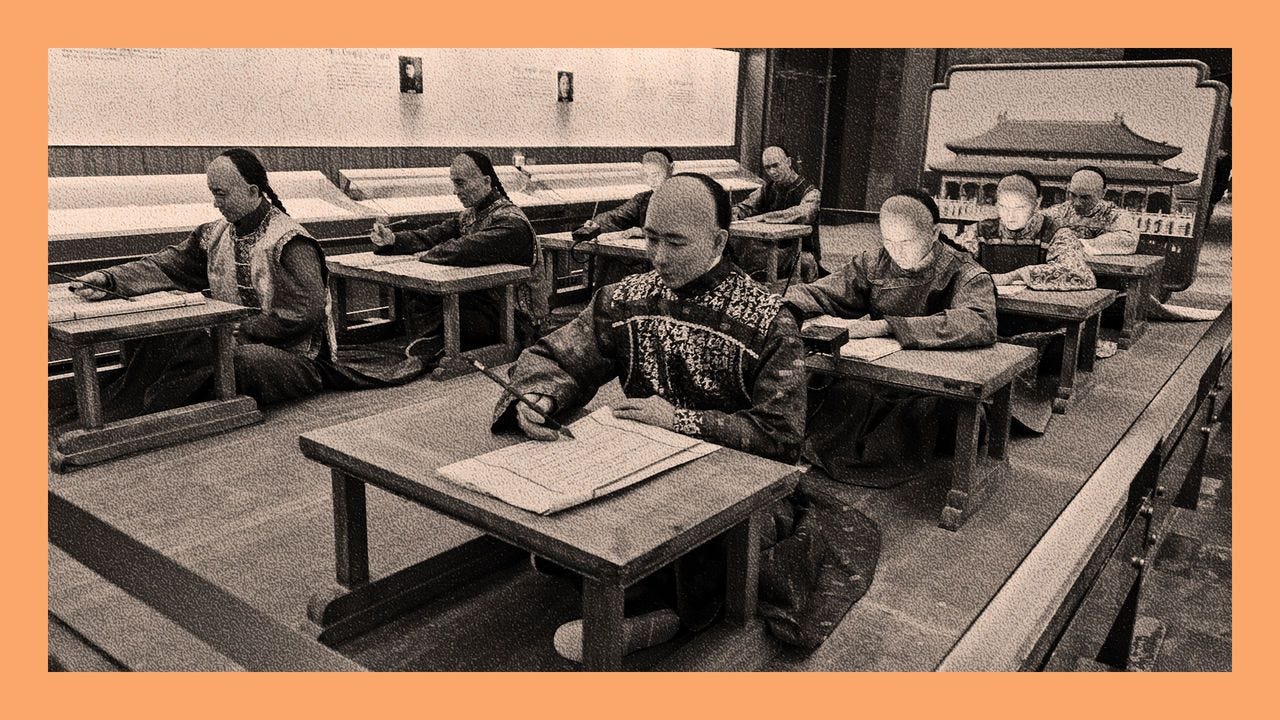

The Civil Service Exam

About a thousand years ago, the Chinese Song dynasty began to systematize the way it selected its bureaucrats. The civil service exam was, initially, one of the several ways of gaining a career in government. Over time, it became the only route to the most prestigious positions.

Essentially, it was a memory test. Examinees were asked to respond to questions on the classic Neo-Confucian texts, nine books that they needed to be able to quote from in lengthy essays which they had three days to compose in surveilled isolation. Test takers were also expected to be able to compose poetry. Both their essays and their poetry needed to follow traditional forms and observe unstated etiquette which was reinforced by generations of successful students becoming examination assessors.

In theory, the purpose of the exam was to find capable ministers for governing a vast empire. But the traditions of the test became sacred in themselves and the assessment became rigid. So, the purpose of the exam became, in effect, finding who was best at taking the exam.

The successive dynasties did have another goal though. Examination-qualified civil servants progressively replaced people who held authority due to being in aristocratic families. While those families would persist in China, their children suddenly needed to pass the exam in order to hold authority. This centralized the imperial household as being the authority who could grant a prestigious position.

More importantly, perhaps, it sent a message that anyone could rise to the top. Because, legally, any man was allowed to take the tests. Of course, having a boy study, instead of work, for over a decade was something that only fairly privileged families could afford. But many outside the traditional aristocracy could afford it.

The message this sent people was they were responsible for their own success. The doors were open and taking this one test could change your life.

By the same token, if you failed it was because you didn’t study hard enough. Don’t blame the system; blame yourself.

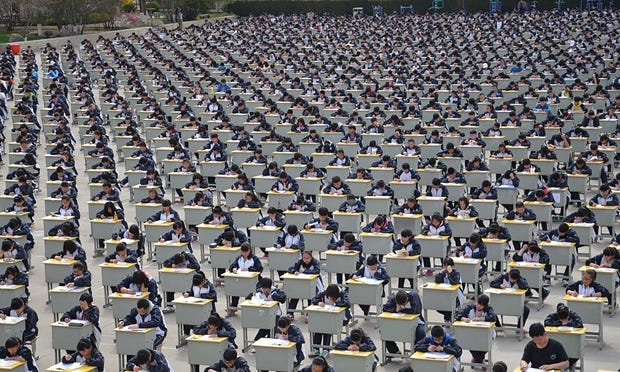

The Gaokao

While modern China still has a civil service exam, that is no longer the sole path to prosperity. Instead, the focus is on the national college admission test, the Gaokao.

Every student who wants to go to college takes the same test at the same time. The topics have moved from Confucian classics to math and language, but there remains a heavy emphasis on memorization. Students are expected not just to know the right facts but also how to write about those facts in a way that will be well received by graders using a specific assessment rubric.

Unlike in the United States, success on the Gaokao is almost solely responsible for determining which domestic university you can attend. There is a clear delineation of which institutions are “the best” and attending there directly correlates with your post-graduation job prospects. So, succeeding on this test really can be the golden ticket for a student who lacks privilege.

Of course, most students who succeed come from just as much privilege as their aristocratic forbears in the Song Dynasty. While there are exceptions to the rule, the students who tend to do best on the exam are those who attend the most prestigious schools in the wealthiest areas of the biggest cities.

And everyone knows that’s the case. It’s not a secret. But they also know that every year, some students defy the odds. Because defying those odds and rising above your station is possible, the failure to do so is also a reflection on your choices. If it’s possible to succeed and you didn’t, that’s not a reflection on the system. That’s a reflection on you.

It’s not about an unequal society; it’s about your lack of grit.

Is this whole thing a bit odd?

It’s very easy to write this and conclude something like “China sure is weird with its love of high-stakes testing.” It feels weird partly because the SAT and ACT, despite some attempts to revivify them, cannot compare in their weight to the admissions process, even at colleges that require them.

I think this is partly because the United States does not have a tradition of ascribing absolute hierarchies to different universities. Yes, there are national rankings. Yes, most people have some sense that Harvard is a “really good college.” But it’s common in the US to hear about students who choose to study at their local university instead of going to a more “prestigious” institution. They may even have good reason to believe their education will be better at a college that few have ever heard of.

That kind of calculus is not present in China because of the direct connection between college attendance and job placement. Again, Yale grads may sometimes get a leg up with that line on their CV, but they’re equally likely to lose out in the interview to someone who went to Ohio State because other factors will be more important to employers.

We still love a big test

If the college admissions test bears less weight in the United States, though, that does not mean we have nothing to match the Chinese experience with examination culture.

Think of the MCAT. It’s a common aphorism that pre-medical students should just go to the cheapest university they can because they will get into med school based off their MCAT score. It’s a test that can help you overcome any background.

It’s not just school admissions either. Every enlisted member of the US military has to take a standardized test called the ASVAB before joining. Their test results determine which jobs they are allowed to do, no matter their personal preference. Every public library in America has study guides for how to succeed on this test.

We even have comparable tests to the ancient Chinese civil service exam. Anyone who wants to work in the State Department as a foreign service officer must pass the standardized FSOT exam before they’ll even be considered for interviews.

There are plenty of other examples, but they have something in common: we actually care about the results.

College admissions tests are less universal today because we don’t treat access to the university as something to be safeguarded.

By contrast, we only want “the best” to be our doctors or to do the most difficulty military jobs or to represent the country abroad. Since defining “bestness” is always difficult, we defer to an exam to give us a number to prove that the people in those roles deserve them.

We also use the tests to tell ourselves that those people have earned their success and responsibility: “Maybe if you had studied harder, you could have had the job they got.”

We can defer and accept their place in the hierarchy partly because we know that we could have done the same. But maybe we just weren’t gritty enough.

This is glue for social cohesion.

When people see their shortcomings as a product of individual choices instead of social systems, they are more likely to resent themselves instead of their circumstances. This takes pressure off social systems to be responsive to change. It allows societies to celebrate individuals who defy the odds without having to ask many hard questions about why those odds are so hard to defy.

-Matt

Thanks for writing this Matt. Really interesting.

Not exactly the same as standardized testing, but reporter Jake Adelstein had to take the very intense Japanese language exam to be eligible for hire at the Japanese newspapers. His writing about that exam (and in the 90s was the only American to have ever passed it) is pretty interesting.