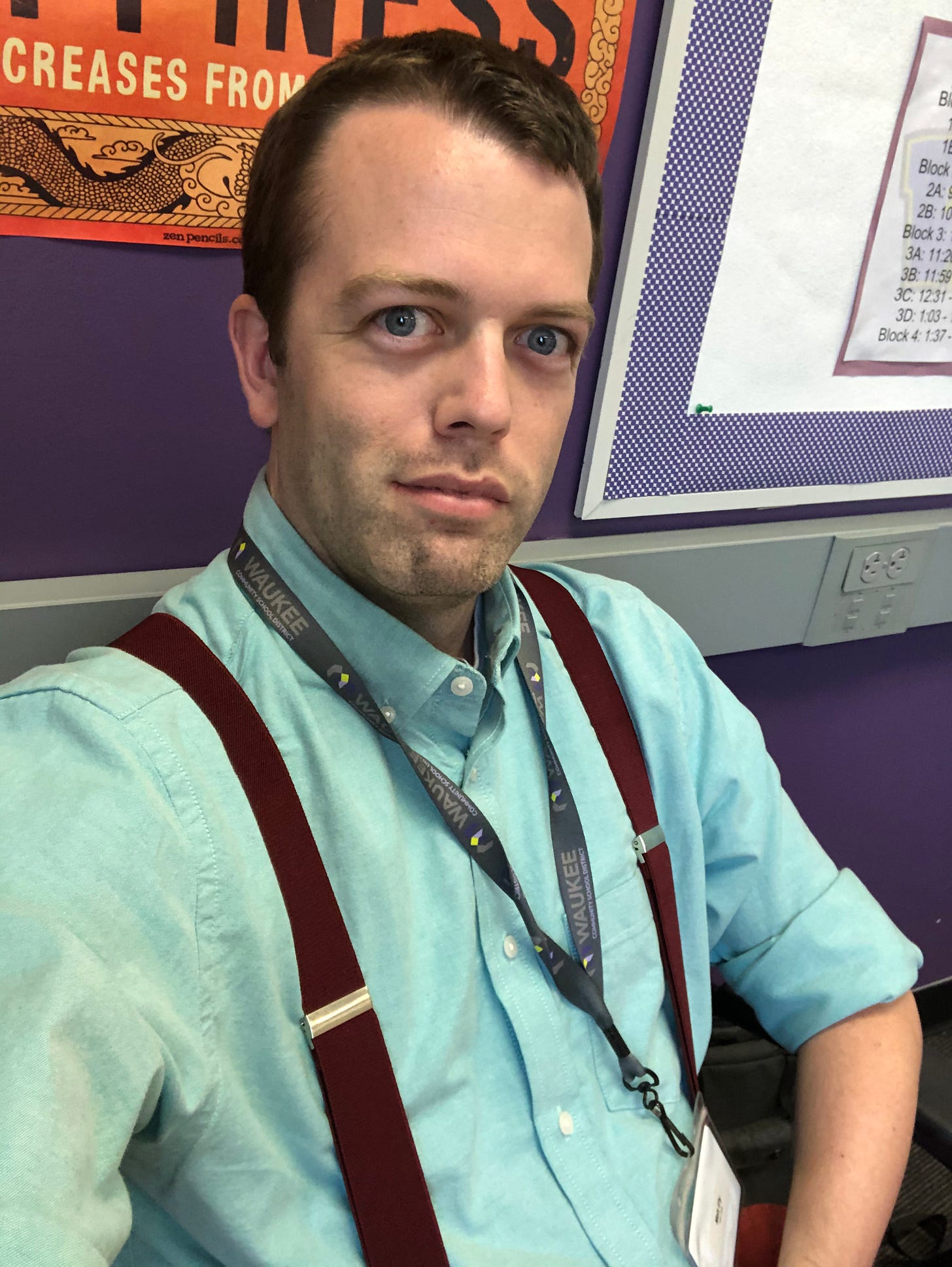

I used to be a public school educator. I taught social studies at a high school in central Iowa.

I wore suspenders every day as if it were my uniform. There were lots of things I liked about teaching, but I quit in order to begin my PhD in Indiana. Perhaps that was easier for me because it wasn’t the first profession I’d quit.

The first profession I quit was also the first I ever had. I was an Army officer for seven years after college. This picture is from my final day in uniform.

How does service end?

I want to talk about quitting, how we justify it, and how the act is understood.

When I quit the Army, that act was familiar. No one really expects people to stay in the military indefinitely. Even those who stay until “retirement” leave after twenty years, meaning that they will begin a new career after retiring from a military one. Perhaps we have inherited a cultural consciousness about it from generations of draftees, but one way or another it’s expected and unobjectionable for military service to be to be temporary.

Of course, military service isn’t the only kind of service. You could define any public sector job as service because the mission of the organization is, ostensibly, directed toward public goods instead of private gain. You could use it to describe working in the non-profit sector. It certainly qualifies for volunteer work. I think we use the word for any kind of work not centered on profit, though exactly how we use these words is probably more contradictory than we like to think.

But if military personnel are the group most commonly associated with “service,” teachers are not far behind. They are similarly burdened with addressing the issues of the public whether they’d like to or not. They similarly become symbols of virtue or vice, depending on who’s talking. While both careers can provide good livings, neither is one that is typically done “for the money.”

They are also employed in their millions, just like military personnel, and they are the most numerous class of public employees in the United States. In fact, there are about 2 million more public educators than there are active military personnel in the US.

AND YET

We don’t know how to talk about teachers quitting.

When I was in the military, I saw people quit all the time. Because we all had years-long service commitments, it made sense to leave once yours was done. Staying in was praiseworthy, but leaving did not require justification. It was expected.

We don’t have a handy phrase like “Thank you for your service” for teachers. Unlike the military, teaching can be permanent. Most of us have encountered career teachers, people who entered it in their twenties and remained in a teaching role until their full retirement. It’s a career you can do for forty years or more. No one will stop you.

So because you can continue indefinitely, doing anything else is a kind of quitting we don’t have shorthand for. Unlike the military, it has to be justified.

The pay wasn’t good enough.

Or the leadership at my school was bad.

Or I got tired of working with kids.

Or I want to go back to school.

Or I want to focus on my own family.

Or I want to start a business.

Or I’m burnt out.

Or I need to try a new career.

Or I don’t believe in the education system anymore.

Or any number of things. Each justification seeks to evoke a response. It asks us to pity them, to blame the system, to respect their determination, to laud their virtue. It asks for us to say something more specific than “Thank you for your service.”

But what’s odd here is that every act of a teacher quitting must be justified at all, that it must be explained.

What do we think we’re doing when we’re teaching?

This entry is mostly just an observation on my experience. But having quit teaching, at least for now, it did make me ask where the impulse to justify comes from. And is there any way to get around it?

My current theory is that we collectively view teaching primarily for what it isn’t.

It isn’t about the money. It isn’t easy. It isn’t respected. It isn’t a growing industry.

I don’t know that any of those perceptions are true, but they are common narratives. So, what kind of alternative is there?

If we view teaching as a kind of “noble sacrifice” and we ask teachers to view themselves as nobly sacrificing, that validates a mindset of absence. Teachers must embrace the fact that they are doing without, that they are good, that they are better off not having what other people have.

You’ll eat your social virtue, and you’ll like it.

But what if we reframe the mindset of sacrifice to one of selfishness?

This is a prickly approach because plenty of people already think teachers are selfish. They think teachers are overpaid with their tax dollars. Or they just get summers off because they’re lazy. Or they just want to brainwash children for fun.

A meaningful segment of the public resents and distrusts teachers based on a misperception of the profession. That kind of animus would make anyone shy away from thinking of their job as selfish and motivate them to think of it sacrificially.

But when I think about teaching as sacrifice, my tank gets empty. I focus on what I don’t have.

Thinking about it selfishly gives me so much more. I can think about how lucky I am to not have to worry about a company’s profits. I can think how few emails I have to send and how few meetings I have to attend. I can think about the fact that I get to perform every day in front of an audience. I think about how cool it is to be a staple in young people’s lives. I am selfish for attention and validation and authority.

Teaching was a place where I could achieve so many things that were impossible elsewhere. It’s not the easiest job, but no job worth doing is. When I reframed my thinking as opportunity-centric instead of sacrifice-centric, I enjoyed my job more and was able to laugh off the public critiques more easily because they seemed so irrelevant to what I was actually doing.

The haters were no longer loathsome, they were just out of touch.

So I quit happy

When I quit, I did not see myself abandoning a noble sacrifice. I saw myself giving up an awesome opportunity in teaching, an opportunity that I loved selfishly and personally.

But I didn’t feel the same need to justify it because the reason I quit was for another opportunity that I loved even more selfishly, one that was even more personal. I wanted to pursue a PhD, not for the greater good. I wanted to do it because it’s fun, because it’s rewarding in itself.

I was a teacher for my own reasons. I am a grad student for my own reasons. Both things make me very happy. And because I saw both as opportunities, not sacrifices, I didn’t really care whether anyone thanked me for my service.

-Matt