Hermeneutic reconstruction and the worlds we seek

Reflecting on how and why we might ask people questions

When I began this Substack and wrote the "About" section, I said that this would be a public-facing journal. That may not be the best description, but what I was trying to indicate was that I’d use this space to show how I was thinking through issues in higher education. This is a space to practice my conceptions and make them more concrete by writing them. This one is going to get pretty abstract, but I am going to roll with it.

I would like to examine the term “hermeneutic reconstruction” as I understand it. I am not making absolute claims about its meaning, nor am I making hierarchical claims about its value in respect to other forms of inquiry. I am going to revisit some issues I raised in a previous post about social science by being more specific about the methods I was referring to.

What are we doing when we do things qualitatively?

What I’m writing about today lies squarely in the realm of qualitative inquiry. The distinction between qualitative and quantitative is about whether the thing you’re looking at is a number or not. While you can use arithmetic techniques on numbers, you can’t use them on words. You can turn words into numbers, but that’s something else.

When you’re examining words, i.e. doing qualitative inquiry, you are entering into the world of social relations. Every word has an author (or speaker), and that author uses their words to try to bridge the gulf between “me” and “you” and create shared understanding.

This is what I am doing right now. I have all the thoughts in my head, but I conceive using more than just words. I am trying to take the whole of my mental experience and translate it into a text that will get your mind to go where my mind is. We are always doing this.

In broad terms, the sciences examine physical relations between objects. The humanities examine interpretive relations between humans and the objects of human labor. The social sciences examine the way that humans communicate with one another.

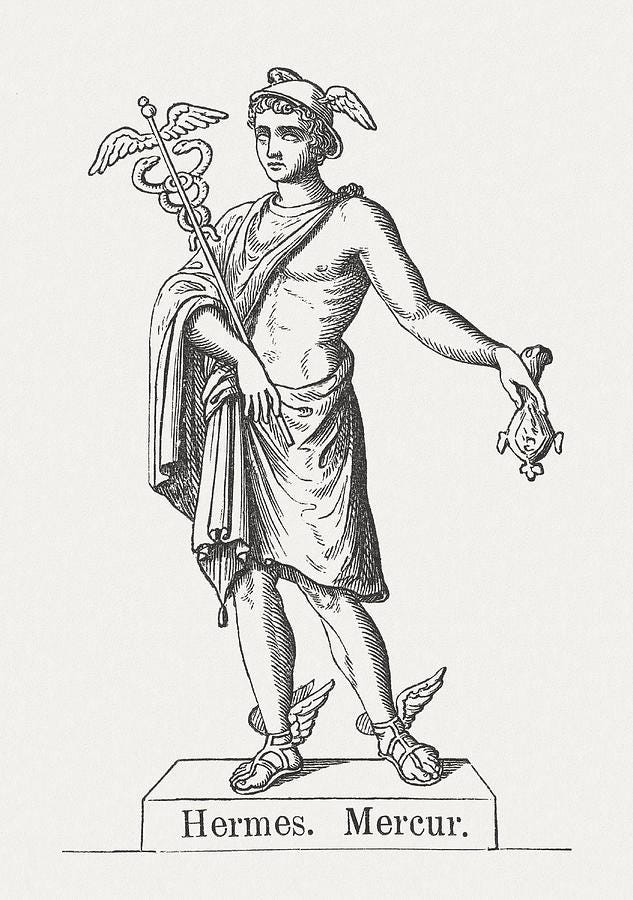

This is where we get the word “hermeneutic.” Hermes is the herald god, the ancient Greek divinity who flew between the gods and humankind. His role was to bridge the gulf in understanding between these two distant kinds of beings.

Until I started my PhD, I only heard “hermeneutics” in the context of Biblical interpretation. This makes sense because that’s where the term originated. It began with German theologians endeavoring to understand the writings of the Bible within the context of their writing instead of taking them at face value from a contemporary lens. This process sought to bridge the gap between an ancient writer and modern reader, allowing for a translation not just of words but of the context that sits outside the text itself.

The act of reconstruction

Hermeneutics seeks to approach a text from another time and place and translate it to our own time and place. This is important if you want to understand the Bible. But it’s also important if you want to understand another person.

The insight behind hermeneutic reconstruction is that every person needs to be translated.

Communication is possible because of shared cultural environments. The more overlap you have with someone in terms of your language, experiences, and interests, the more deeply you can communicate with them. Perhaps more importantly, the more your personal cultures overlap, the less explicitly you need to communicate. Instead of needing to spell out your thoughts and feeling with words to be understood, people who know each other well can communicate with gestures, vague references, or body language.

The people who know each other best can communicate with a personal language which, if observed by an external party, would lose much of its meaning. For example, if I look at certain people, raise my eyebrows and say “Craisins,” that will bear clear implications and references. But to most people, that would sound like a meaningless allusion to dried cranberries.

Hermeneutic reconstruction, then, is the process by which you partner with a human subject to take the implicit meanings of interpersonal communication and make them explicit, such that an outside observer could understand all that is implied in a shared cultural environment of which they are not a part.

The human partner element is critical because, unlike theologians, we can reconstruct alongside our original authors. A social scientist who wants to understand a person’s experience can ask them about it. The challenge is you have to listen.

Whose world do you inhabit?

In my last post on this topic, I focused on the fact that the scholar should be learning from their research partners, expecting that they will have nothing to add. The point is not to interpret another person through a theory and fit them into your narrative; it’s simply to understand their narrative on their terms.

What I failed to address was why this was a valuable approach. There’s nothing morally superior about conducting collaborative research. The issue is what kind of information you seek.

Most of the time, when we think about “truth,” we are thinking about “the truth” about “the world.” We assume that truth is a universal, verifiable fact. These kinds of truth claims are “objective,” meaning they function as an “object.” Objects are external to human consciousness, such that their attributes can be confirmed by different observers. You could say that an objective claim has “multiple access” because I am just as capable of seeing and understanding it as you are.

We tend to treat “objective” here as a synonym for “real.” It’s typically contrasted with “subjective,” which is often interpreted as “less real” or “less valuable.”

What “subjective” means, though, is belonging to “the subject.” The subject is the initial actor or, in our case, the speaker. So a subjective claim is a claim that only the speaker can verify, AKA “privileged access.” These are claims like “I feel…” or “I think…”.

Now it’s easy to say that subjective claims are false or unimportant because they belong only inside the subject’s mind.

A claim like “I feel like the Cubs are going to win the World Series this year” is not objectively true because we can observe that Cubs are not in the playoffs. That is a claim about the world because it concerns the physical and the observable. But the claim is still subjectively true because the subject does indeed feel it to be so.

Subjective claims are not about the world. They are about my world. In order to understand a person, you are looking to reconstruct their world, not the world. This is what social research is for.

You can continue this to include value claims. These are claims like “We should…” or “Everyone ought to…”. Here, the subject tries to describe our world, the moral universe that they imagine themselves to share with other people. Even though not everyone will agree with their value claims, they should.

By categorizing and labeling these claims, among others, we take implicit and internal communication and make it interpretable to an outside actor.

Means of reconstruction

The purpose of hermeneutic reconstruction is to bridge the gap between persons and reconstruct their world. You will analyze observations, interviews, focus groups, and other social settings to provide an proposed interpretation of the subject. Then you will “member check” with that subject, allowing them to add their own commentary on your interpretation.

The interpreter will often not provide single meanings. Instead, they can develop “meaning fields,” or ranges of potential interpretations for ambiguous acts or statements by a subject. The interpreter can also analyze non-verbal acts, tone, and implications. All of this serves a starting point for them to collaborate with the subject and work towards a mutually intelligible interpretation of that subject’s cognition.

This makes explicit the entire “speech act” of their cognition. Every means by which we communicate can be included in this speech act. Every speech act is an effort to share consciousness, to make someone else see the world the way the subject wants them to see it.

Reconstruction is a way to make that more possible, to help a person explain themselves such that they can be more clearly understood by other people. But, importantly, it’s also a way for the subject to self-examine.

Reconstruction as liberation

Oftentimes, the claims we make are implicit, even to ourselves. Or we will make claims we believe to be objective which are, in fact, subjective or value claims. We can be beholden to narratives that we do not understand for reasons that we cannot explain.

At its best, hermeneutic reconstruction is not just about an observer understanding a subject. It’s also about a subject learning to understand themselves.

As a method, it’s born out of the critical tradition. This means lots of things to lots of people, but for something to be “critical” it must seek liberation. So, in this case, the subject engages in collaborative interpretation in order to be liberated from the claims they hold implicitly. By making them explicit in partnership with the observer, those claims can be examined and lose their controlling power.

Human cognition is never caused because human cognition is not a physical object responding to immutable laws. While we are influenced by our environment and our conditions, everyone is always capable of transcending the narratives which they are expected to hold. This act of transcending, of deciding which narratives we choose to hold, is the kind of liberation that hermeneutic reconstruction seeks.

Of course, liberation is optional. Human subjects don’t need to agree with an observer’s observations. And observers don’t need to agree with a subject’s self-perception. The observer can easily be deceived. The subject can easily deceive themselves.

Hermeneutic reconstruction is not magic. It does not produce perfect outcomes. But it’s important to recognize that there is no way of doing social research that produces perfect outcomes. Human cognition can never be quantified, condensed, or described perfectly.

Every time we try to describe ourselves or are described, we likely think “Ah, but that’s not quite true.” Every effort I take to describe who this “me” person is falls short because I feel myself to be more than my words can contain. Just as my cognition can choose to transcend any external description, I cannot help but transcend my own efforts at self-description.

So the point is that we live for half measures. We can describe ourselves in part, but not all the way. We can observe someone in a new way, but not in every way. We can build a bridge to get closer to another consciousness, but we can never arrive at the other side. Not fully.

But we can try.

This is one way to try.

-Matt

Deep. Reminds me of Einstein's theory of relativity.

Your subtitle is helpful. Thoughtful, well-intentioned questions are very liberating. This description of how we might better arrive at such questions is helpful.